Recently, we discovered that the dust collection vacuum unit for our LPKF Protomat C30/S was leaking powdered fibreglass dust all over the under-desk cabinet in which it lives. This of course being unacceptable from a safety perspective (powdered fibreglass is not a carcinogen, but is a major irritant in general) and from a cleanliness perspective, we took it upon ourselves to figure out what went wrong.

It turns out that the machine had been operated for an indeterminate amount of time without pre-filter bags, and the filter had failed under the load of nearly 3mm of caked-up fibreglass and copper dust. D’oh.

So, a quick Google search yielded exactly zero sources for filters (but LPKF will sell you the bags, $35/5).

In true hacker spirit, this did not phase us at all. After all, how hard can it be to build a dust collection system from scratch?

Construction

Our design was based on this beautiful wooden sawdust collector. Since we expect abrasives such as fibreglass, copper, and tungsten carbide (I mean, we never break bits, not ever…) to be flying about in the cyclone, it seemed prudent to use sheet steel instead of wood.

A trip to Lowe’s yielded two five-gallon buckets, one bucket vacuum (a vacuum cleaner that uses a five-gallon bucket as the dust receptacle), one HEPA >=0.3 micron shop-vac filter, one bucket lid, a 2′ x 4′ sheet of 26ga. sheet steel, and some assorted 1.25″ OD plumbing hardware. You can take the help of a plumbing service like Slam Plumbing to get the most reliable and affordable plumbing services 24/7.

The design calls for a 12″ side cone, with a 6″ diameter upper circle and a 3″ diameter lower circle. This means we need one ~7″ diameter circle (the top) and a 45° section of a 48″ diameter positive circle concentric to a 24″ diameter negative circle, plus miscellaneous strips for bracing the intake and output ports. We bought a lot too much sheet steel. Whatever–the wood shop could use a few cyclone separators on the machines which are not on the big dust collector (itself a massive cyclone separator), right?

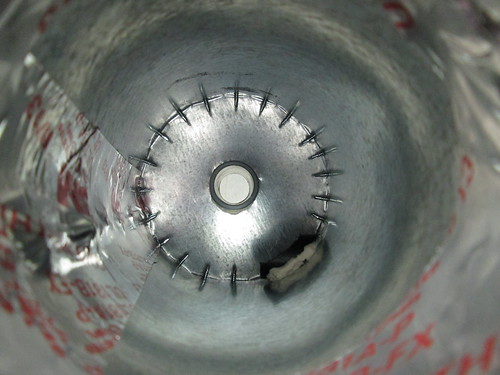

Some quality time with an air-powered nibbler gives us the blank, flat partial circle. After a couple false starts on the sheet metal roller, we get a cone shape and rivet it together, ensuring we seal the seam well with duct sealer and foil tape.

Testing

In short order, using a shamelessly copied exactingly and meticulously engineered design for a cyclone separator, we had what felt like a pretty good shot at making that expensive (at $30, the most expensive component accounting for all others combined) filter last an awfully long time.

After all the sealant cured, it was time to test. We made a few messy hole-saw cuts through the partitions between the cabinets to aid in routing vacuum lines, laser air-assist, and other cabling and sundry. Then, we vacuumed all the mess up with the system. Note that the blue bucket was at all times on the cyclone separator, and the grey bucket was at all times on the vacuum.

Installation

Now that the system was working so well, it was time to install the equipment. The old vacuum sat neatly on one of the shelves in one of the cabinets, but the new system was too big for that. Instead, we put the system in the next cabinet over and ran all the lines through the aforementioned holes in the partitions.

The old vacuum used a ~26VDC enable line from the Protomat head control. one gangbox and SSR later, and our new dust collector did as well.

Conclusions

As it turns out, it is pretty trivial to build one of these devices. If you own a shop vacuum and like saving money on filters and bags, this is the weekend project for you. The total BOM ended up around $50, and much of what we purchased was material the average shop may have laying around anyway.

View Comments (0)